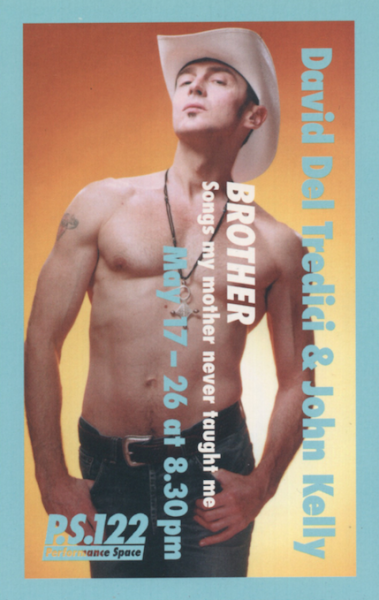

Brother (2000)

Texts, Choreography, Direction, Video Sequences/Animations: John Kelly

Music: David Del Tredici

Lyrics: John Kelly

Additional Lyrics: Allan Ginsberg, Paul Monette and Jaime Manrique

Set Design: Scott Pask

Produced by Alyce Dissette

Workshop production: Yale Repertory Theater, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, March 2001. Premiere: Performance Space 122, New York, May 2001

+

Brother was my debut as a lyricist. I was certainly aware of Pulitzer Prize-winning composer David Del Tredici’s work and stature, and I was surprised and thrilled when he unexpectedly showed up backstage at the Westbeth Theatre Center after a performance of Paved Paradise. He said then that he wanted to work with me. As it turned out, he meant it. We found ourselves together at the MacDowell Colony in 1997, and one day I gave him some poems to read that I’d been working on. The next day he said, “John, come over to my studio.” He’d set one of my poems to music. That was the beginning. The following summer at Yaddo we completed work on the cycle, and I began to learn and perform the songs.

Brother is a song cycle for countertenor and piano––an emotional, sonic journey through vignettes of a gay man’s life. The texts, which include additional lyrics by Alan Ginsberg, Jaime Manrique and Paul Monette, focus primarily on love––desired, gained, lost, mused on, murdered. Our goal is to bring to theatrical life the relationship between piano, singer, music and words. For me, this work continues my infinitely challenging quest to understand what it means to be a man.

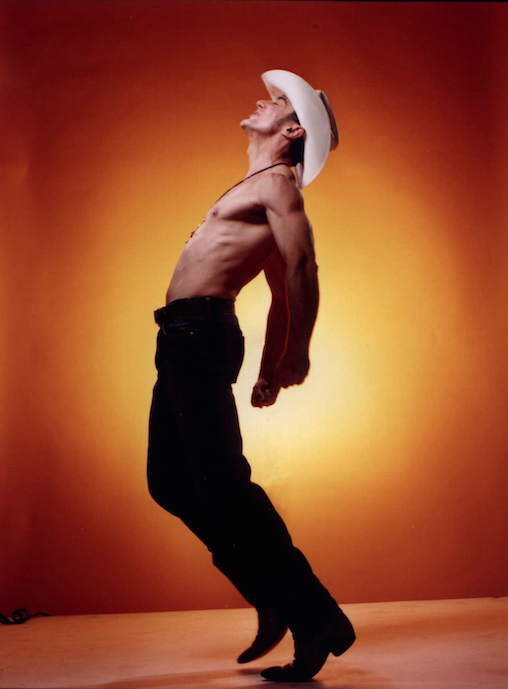

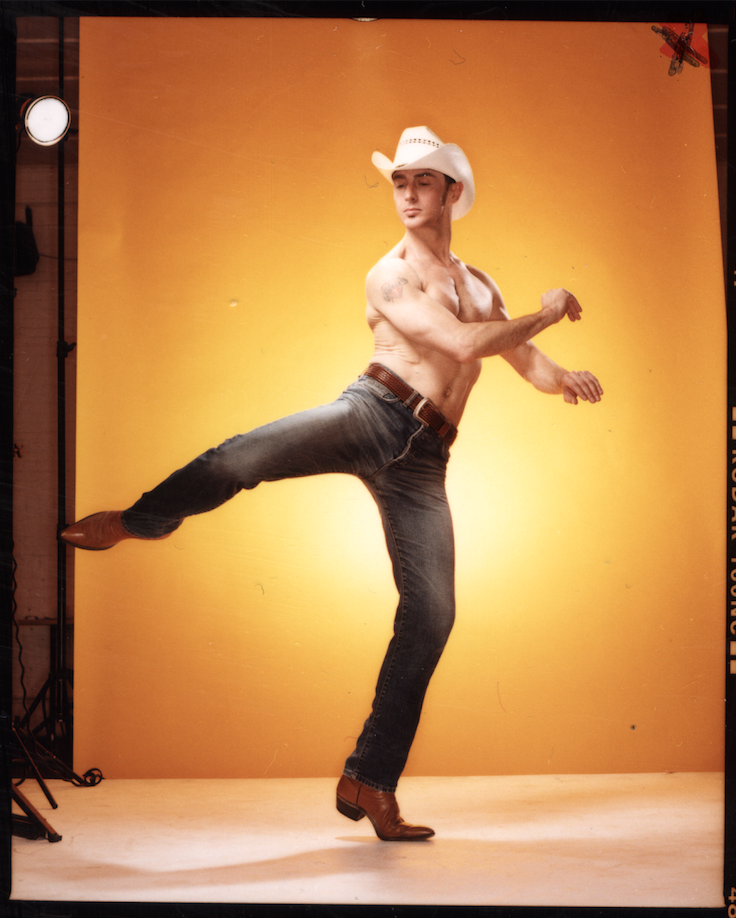

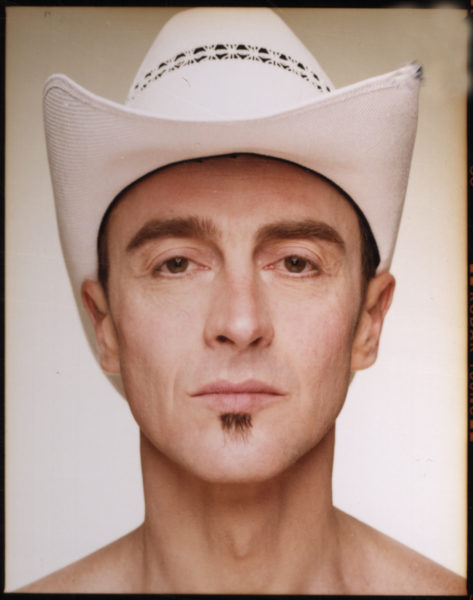

A man can be rendered in an extreme or obvious way––a mohawk, a kilt, a cowboy hat––or in a less visually blatant manner––powerful, vulnerable and naked, stripped of clothing as protection, as socially defining garb. The great challenge for me now appears to be exploring my humanity––my relationship to the world and to the events that fill it and thus fill my own experience as well. Sure, I imagine my work will always contain an element of play. But wisdom and understanding have become ever more important to me. They define my spiritual life.

I am finding that my theatrical choices begin much closer to me now––the man, no longer a boy, not a woman, but a soul who carries with him (an atmosphere) A degree of experience, survival, achievement, compassion, courage and peace. An aging angel, his face lined, his hair thinner, his shoulders more powerful, his vision focused simultaneously inward and outward, mindful and not fearful, trusting but not careless, accepting but not jaded, able to savor and to plan, to recall and to imagine. A man who has survived plague, wept over loss, raged over injustice and howled with laughter. A man who is able to be present, accept life and death in the same breath and still remain in the game.

A man who is just scratching the surface and wouldn’t have done it any other way. No regrets.

IIIII

LOVED

I CRIED

I PINED

I WAITED

I WATCHED

I THOUGHT

I FANCIED

I DREAMED

I SPECULATED

I ANALYZED

I LACERATED

I CURSED

I CHANGED

I BREATHED

I WAITED

I WILTED

I TRAVELED

I MUSED

I PRAYED

I STAYED

I YEARNED

I RETURNED

I SPOKE

I SAW

I REALIZED

I RESIGNED

I WROTE

I’LL LIVE

© John Kelly 2019/2001

Photo by Martin Scholler

PRESS

Linda Yablonski, Off-Off color: Obie-Winner John Kelly Tunes into Modern Love With Brother, Time Out New York, May 17, 2001

For a performer who learned stagecraft by doing drag at the Pyramid Club in the East Village, John Kelly has become quite a class act. Last year, the actor, dancer, choreographer and vocalist appeared on Broadway in the Tony-nominated musical adaptation of James Joyce’s The Dead. He had already won two Obie Awards for his own dance-theater work: one in 1987 for Pass the Blutwurst, Bitte, an homage to the Viennese artist Egon Schiele; the other in 1990, for Love of a Poet, a staged recital of Robert Schumann’s Dichterliebe. He has also directed opera in both Europe and New York. Nonetheless, Kelly is probably best known for his tour de force performances as Dagmar Onassis, the Maria Callas manque he brought to Carnegie Hall in the early 1990s, and as Joni Mitchell in his staged concert, Paved Paradise. (Mitchell caught his act three times. “She gave me her dulcimer,” he says.) Kelly returns to the East Village this week in Brother, a piece of stark musical theater he created in collaboration with the Pulitzer Prize-winning composer David Del Tredici.

A classical composer and an irreverent performance artist may not seem a likely creative team, but they found their ideas compatible when they were both in residence at the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire in 1998. Brother’s episodic narrative is structured around nine lushly Romantic songs that Del Tredici has set to poems by Alien Ginsberg, Paul Monette, Jaime Manrique, Lewis Carroll and Kelly. The show, which traces a gay everyman’s relationship to love, sex and death in America, is a far cry from musical comedy, but it’s not without humor, and it takes full advantage of Kelly’s multidisciplinary approach to theater.

Accompanied by the composer on piano, Kelly sings, dances, acts and changes costumes against a backdrop of affecting videos he made himself. He prepared for a segment of the show featuring a tense Western line dance by going to the Big Apple Ranch, a club near his Chelsea apartment, every Saturday night. “I got hooked,” he admits. He’s still going.

Kelly has a habit of jumping into things feet first. Now in his forties, the trim six-footer originally trained as a dancer and a painter; he began studying voice only after his wee-hours singing debut on Pyramid’s opening night in 1981. He has since developed a three-octave range that completely wowed the audience at Alice Tully Hall in February, when he and Del Tredici previewed a few songs from Brother during WNYC’s A Great Day in New York concert. Listening to a tape of the live broadcast for the first time, Kelly is amazed when prolonged applause and loud cheers erupt for the duo’s performance of a Paul Monette ode to a lover lost to AIDS. “I didn’t think they understood it,” Kelly says, wide-eyed. He is pleased to know better now. “The music seduces people,” he says. “Then I hit them over the head.’

Tony Phillips, Big Brother: An Interview With John Kelly And David Del Tredici, Next Magazine, 2001

They have enough awards between them-Obies, Bessies, even a Pulitzer Prize-to prompt the old Joan Rivers’ “Where do you keep your Oscar?” stand-by. Not willing to take the bait, composer David Del Tredici kicks things off by talking up a Gay Male S/M Activist (GMSMA) dungeon demo he’s planning on attending on the weekend. “It’s very exotic-some of the things you see–people with needles stuck in them all over.” And just like that we find ourselves in an exhaustive conversation about nipple play. “People with rat traps on their nipples,” performer John Kelly adds, cataloging the sights to be seen at the GMSMA demo. Del Tredici laughs, “We know where you’ve been recently.” Once it’s clear we’re all talking about the same person-our favorite bartender at the Lure-we take a wistful pause before Del Tredici continues, “I love him, I always talk to him.” I add that I consider him a New York institution while Kelly offers, “I guess some people have more G spots than others.”

At this point, the occasion for a drop into the sunny Del Tredici loft in the much-coveted Westbeth–artist housing in the former Bell Labs building–should be explained. We’ve gathered to discuss the song cycle for countertenor and piano called Brother--running at P.S. 122 though May 26th-that Tredici has set to the poetry and lyrics of John Kelly. “We’re hoping to come together,” Del Tredici, who greets me at his front door in the ultimate “I live here” statement-blue and green striped dress socks coupled with a serious leather vest and black jeans-explains, “We have totally different audiences.” He continues, “In the classical world, there’s the downtown scene, which is much more open, and then there’s the more uptight uptown scene.” He thinks about that for a moment and adds, “Even the downtown scene is sort of square. The other thing is sex is somehow not allowed.” Kelly-who moments ago came clomping through the back door of the studio in black engineer boots and blue jeans-sums up the tricky territory of the classical world. “It’s either dealing with dead artwork that people are bringing back to life,” he says, “Or living artists who are creating in the shadow these great artists.” Kelly’s tight white v-neck tee shirt stops just short of a tattoo on his right arm with a cursive “Dagmar” flowing across a red heart.

Dagmar is a reference to Kelly’s 1993 creation from the transcendent performance Light Shall Lift Them. The New York Times described the character of Dagmar as “resplendent in an emerald-green gown and overweening beehive.” Kelly, an art on his sleeve type of guy, tosses down a pack of temporary tattoos for Del Tredici, who’s thinking of inking up. Kelly tells Del Tredici to experiment with a less permanent look first, but all he’ll say about Dagmar, who is modeled on a Callas-like diva, is, “I’ve stopped doing her, but I’m in touch with a lot of real elements of her.” He has a lot more to say about Callas herself, “She had such a tragic life and everybody always thought she had an abortion, but as it turns out they have proof that she did in fact have the child.” Cleaning out a storage space and an exercise from the book The Artist’s Way collided, leading him to sit down with a dusty recording of Callas’ last Norma, which she was unable to finish. “I thought it was would be awful, like watching a snuff film, and then I sat and listened to it,” Kelly says, “It was obvious she wasn’t up to par, but it was not as bad as I thought it was going to be. It was kind of tragic in a way.” He then explains his own brush with performance anxiety while doing Dagmar at Carnegie Hall. “It was soon after my lover had died and I was singing this Bellini aria and toward the end, it was this very soft part where the voice just goes on its own. I literally got choked up and I had to stop. I just knelt there and calmed myself and relaxed my throat. Then I got it back. It took 20 or 30 seconds, but it was the most electric moment because the audience clearly knew.” He understates, “It’s hard to cry and sing at the same time. You have to negotiate that because when you’re all choked up, you’re literally all choked up, forget about singing.”

“You can speak and cry,” Del Tredici adds with a strange optimism that offers a glimpse into their work process. The song cycle Brother brings together two completely diverse performative careers. Kelly calls the piece “very episodic vignettes from a gay man’s life.” Of the song selection process, Del Tredici jokes, “He took all my hits, John has a very good ear for spotting the best ones.” Indeed he does, taking on everything from a tender Joni Mitchell tribute called Paved Paradise (he closes Wigstock and even opened Natalie Merchant’s Ophelia tour as Joni) to Bartell D’Arcy in the Broadway musical of James Joyce’s The Dead. Kelly, who trained as a visual artist and dancer, cut his teeth at downtown venues like the Pyramid Club and The Anvil in the ’80s. “I used to sing in clubs at two o’clock in the morning to music minus one records,” he says, “My real schooling was the clubs. I performed at the Pyramid the night it opened. I used to go to the Anvil and sketch. I saw Tanya Ransom lip-synching Nina Hagen and it changed my life.” Kelly then brings up the subject of drag: boy-drag, classical-drag, drag-drag, calling it “a way for me to get back onstage and realize that I wanted to be onstage. I started painting my body instead of painting canvases, literally.”

Del Tredici ponies up an interesting drag story of his own. When the prestigious Composers Recordings, Inc. (CRI) put together a disc of living, gay American composers, it was considered a milestone for classical music-a world Kelly calls both “really, really conservative” and “very intense turf.” At first hesitant to tell the story of the photo shoot for the disc, Del Tredici warms up once it’s clear I completely bow to him for the genius move. “The story is that a lot of composers, who are all gay of course, found out there was going to be drag,” he says, literally dragging this last word out with a laugh. “When they heard some of us were going to put on so much as an earring, they left, saying, ‘We can’t be part of this.'” So what was the actual drag, just earrings? Del Tredici takes a beat, relishing the story at this point, and says, “Well, I had on a dress.” We all laugh and he continues, “And someone else had on a little dress.” Kelly adds, “Faggots have forgotten how to play. In the ’70s there was not was much of a body obsession and there were also smiles and smirks that went along with it as opposed to glacial attitude. That’s all fear-based behavior. I live in Chelsea now after living in the East Village for 16 years, and 8th Avenue is not what Christopher Street was in the 1970s.” Del Tredici explains what he perceives as the unjust gay pecking order, “There are degrees of it, but to go into drag is like the lowest order. Self-internalized homophobia, that’s a real issue, everyone has it.” With unflinching honesty, he explains that because he doesn’t know many, “the whole idea of trannies is kind of frightening for me, whereas drag is perfectly fine now since I’ve done it.” He adds, “Of course, once you do it you’re on the other side of the looking glass,” bringing up Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, a favorite subject.

Del Tredici points to a wall of his studio that’s stacked, salon-style, with images. The one he focuses on is a large black and white photo of himself as a young boy on a tricycle wearing a striped top, what he calls his Alice in Wonderland look. His longstanding obsession with Alice reached a crescendo with his 1980 Pulitzer Prize winning opera-cantata Final Alice. He explains his muse by backing up to explain the classical music landscape of the 1960s, when he first began composing. Tonal composition, typified by the American composer Aaron Copland, dominated the scene. “In Europe all of this atonality started to emerge and it was so thrilling, forbidden and absolutely scary,” he says, “It would drift over to America and it was like the thing to do.” The atonal movement, typified by Vienna-born composer Arnold Schoenberg, chucked tonal composition for a new method based on a series of 12 tones. “Atonality was connected with advancement,” Del Tredici says, “Music has always gotten more and more dissonant, from Bach to Strauss to Mahler, it all gets more tortured. Schoenberg was an extension of that. He just said, ‘Throw it all out, this tonal system, and I’m going to invent my own.’ It was intoxicating.” It was also not embraced by American composers so that taking it up was considered rogue, or akin to what Del Tredici calls “the transsexual operation of the 60s.” He explains, “All these people wouldn’t go there because they were trapped in Americana. Copland had this grip on American people and it was sort of exhausted.”

After establishing himself as America’s leading atonal bad-boy, Del Tredici came back to Alice and a funny thing happened. In trying to recreate that Carroll world of wit, whimsy, charm, I just couldn’t be atonal,” he explains, “It just didn’t seem to fit, so without thinking about it I just reached for tonality and gradually it took over.” He calls Final Alice his “most overtly tonal piece” and adds, “That was the beginning of this neo-romanticism and that was polarized. People newly born to atonality were horrified that someone was going to go back to yet another form of tonality.” Always one for surprises, I ask Del Tredici how his collaboration with Kelly-the paradoxical merging of something so different yet so alike-is perceived by the classical world. He responds, “I’m objectionable on my own terms, forget John, first of all for being gay and being so out about it and also being so tonal. So that’s bad enough, then John joins me, from another world, also openly gay, and falsetto and acting-not just singing–gay subject matter.” He sums it up with a laugh,” It’s all just too much.”

Dan Bacalzo, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, Theatremania.com, May 15, 2001

Back from a stint on Broadway, John Kelly returns to his roots in a new piece at P.S. 122.

“I like to venture through as many doors as I can,” says John Kelly. A writer, choreographer, director, singer, and performer, Kelly is one of the most versatile artists in the business. He’s perhaps best known for his uncanny impersonation of folk rock legend Joni Mitchell, although it would be a mistake to think of him as just another drag queen. His credits include performances at Carnegie Hall, the Joyce, BAM, Lincoln Center, and even Broadway, where he recently originated the role of the tenor Bartell Darcy in James Joyce’s The Dead. His latest project, Brother, is a dramatic song cycle for countertenor and piano, composed by Pulitzer Prize-winning composer David Del Tredici.

THEATERMANIA: How did this collaboration between you and Del Tredici come about?

JOHN KELLY: I was doing my Joni Mitchell show, Paved Paradise, at Westbeth about three years ago. David came to see it. He introduced himself and said, “I’d love you to sing my music.” I certainly knew who he was, but I had never met him. So, I went over to his place sometime later and he played me some music, and I thought it was really amazing. The following summer, we both wound up at the MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire. On a lark, I just gave him a bunch of my poems; next thing I knew, he started setting them to music. He wrote a song cycle to my poetry. Brother is made up of those songs, and also four others that David had written to the work of other poets including Paul Monette, Jamie Manrique, Allen Ginsberg, and Lewis Carroll.

TM: What kind of subjects does your poetry address?

JK: Looking for love. There’s a song about back rooms. There’s a song about having found love. There’s a song about the end of an affair. And there’s a song called Brother, which is about meeting somebody. It was inspired by someone I met in San Francisco; I connected with him and then had to leave. So, it’s the notion of hooking up with somebody but then having to vacate that part of the world, and the frustrations and hopes that exist in that. That poem goes back to 1994. I would write these things in my journal, and at one point I realized I was writing poetry.

TM: That piece provided the title for the show?

JK: Yeah, because it just seemed to include a lot of possibilities. There’s a Matthew Shepard poem and a song about standing by the grave of a dead lover. The show winds up being vignettes from a gay man’s life and experience. But it’s hopefully a universal experience, so that it’s not for a “gay audience.” I happen to think that, at the moment at least, the gay audience is pretty limited in its likes and dislikes.

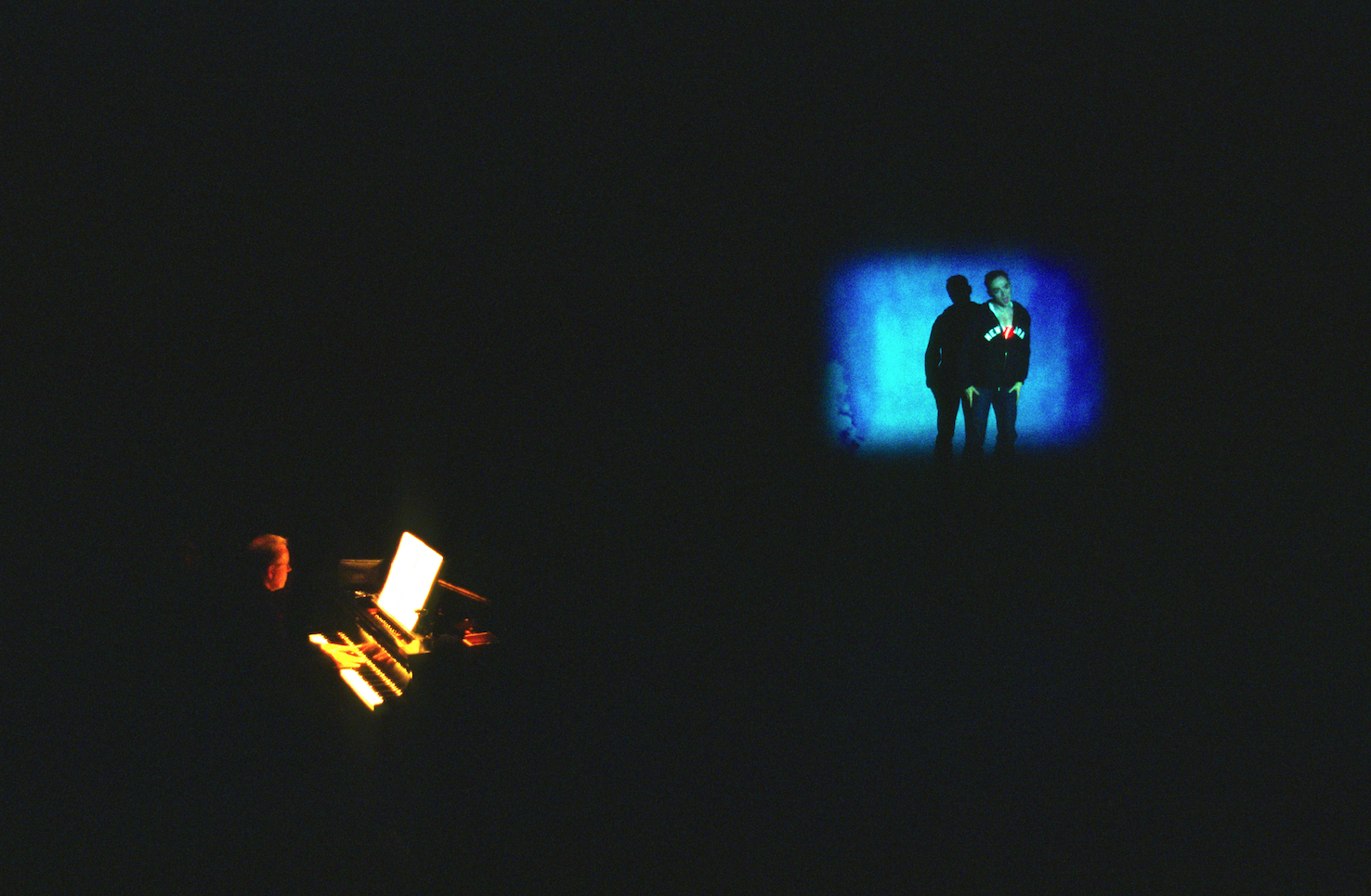

TM: Are you the only performer in this piece?

JK: David’s at the piano, so it’s a duet, in a way. But in terms of stage action, it’s a solo. There’s a video component, which is mostly abstracted. There are some literal images like men’s faces but, aside from that, it’s all objects and drawings.

TM: To switch topics a bit: I hear you have a solo CD coming out later this year.

JK: Yeah, I’m making it right now. I don’t know when it’ll be out.

TM: Does it contain any of the songs from your show at the Westbeth in 1997? I remember seeing that and wishing there was a CD version.

JK: It’s actually pretty close to that. The idea behind it is to have that kind of a mix between Brian Wilson, Tom Waits, maybe a Joni Mitchell song, and Italian art songs–some things written for me and covers of ’60s and ’70s tunes. In my mind, the good ones are like art songs.

TM: I loved your rendition of In My Room by the Beach Boys. I had never heard it quite like that before, and it was just so phenomenal.

JK: That’s such a beautiful song. I never really knew it, so it was kind of new for me, as well.

TM: You mentioned possibly doing at least one Joni Mitchell song on the CD. You’re well-known for your impersonation of her. Obviously, you’re an accomplished artist in a number of fields, so do you find it odd that a lot of people know you just from that?

JK: Yeah, especially when they haven’t even seen the show. “Oh, you do the Joni Mitchell stuff.” “Do you like it?” “Well, I never really saw it.” From my point of view, it says more about the public: The current cultural climate is varied and, sometimes, a large portion of it seems tied to media fame, obsession with youth, and mediocrity. So, I trudge along. I’m the artist that I am, and certain things penetrate the membrane of what we call popular culture and some things don’t. That’s just the way it is.

TM: The other thing you’re known for–recently, at least–is James Joyce’s The Dead. Was that your Broadway debut?

JK: It was my commercial theater debut! I normally just do my own work, but I got tired of being in debt and I thought it would be a good thing to do. It’s so funny: Nobody in that show had ever seen any of my work.

TM: Oh, really?

JK: Stephen Spinella, I think maybe he had seen me do the Joni show. But the rest of the cast didn’t have a clue. At one point the great actress Sally Anne Howe took me aside and said “So what is performance art?” You know, it’s such a divide. What sometimes happens is that people steal from the avant-garde, or they pick and choose and water down certain aspects of it, which is fine, and inevitable, I suppose. Much experimental work is complex, and not easy and not full of “explaination”. I don’t mean to sound cynical and jaded, but you know our culture and our impulse as Americans is to separate and pigeonhole things. We have a hard time fathoming ambiguity. And when things cross over borders–I don’t know, maybe we don’t trust that. I’m one of those artists who does a lot of different things because–that’s just the way I am, curious, and restless. Why do dogs lick their balls? Because they can. Why do I do these things? Because I can, and it satisfies different parts of my psyche. So, The Dead was a great experience. It was interesting to see how that world works, and it happens to be quite a conservative world. At the same time, the stakes are higher; there’s more money and more potential for a certain kind of fame. For some people, that’s their destination, but it was never my destination at all. I think the unions and theater owners can cripple what gets done on Broadway, for instance, because of the expense of doing things. Producers are so seldom willing to take chances. But I thought The Dead was a pretty risky show, a really successful show, and a good piece of work. I was proud to be a part of it.

TM: But now you’re back “downtown,” as it were.

JK: I’m happy to be at P.S. 122; it’s my tribe. And I’m making visual art again, having tangible things to send out to the world.

TM: What are your future upcoming projects, aside from the CD?

JK: I have a book coming out in September, a biography. I’ll probably do another piece next spring, and I have a big ensemble work happening in the fall of 2002 at Dance Theater Workshop. So there’s lots of stuff coming up. I’m back on the boards.

Greg Sandow, Silence And Eccentricity, The Wall Street Journal, March 19, 2001

These events amazed me. I started making lists of things in them that mainstream composers have yet to really pick up on.

Weill Recital Hall was all but silent. Margaret Leng-Tan — tall, erect and dedicated — sat barely moving at the piano. The silence was luminous, lit by her devoted attention, and the audience’s.

This was John Cage’s “4’33”, a landmark of 20th century art, four minutes and 33 seconds in which the performer makes no sound while somehow dividing the work into three sections, in any way she likes. With perfect judgment, Ms. Leng-Tan chose to be both formal and relaxed. To mark new sections, she’d calmly stretch, then strike a graceful pose, leaning her head in her arms, or resting her chin in her hand. She honored and inhabited the silence, making it come alive for everyone.

Though here I have to say that Carnegie Hall (where Weill is located) honored both Cage and his colleague Morton Feldman, by organizing a three-concert festival wonderfully titled “When Morty Met John . . . ” When those two pioneers first met in 1950, not many people knew what silent music was. Carnegie could not quite re-create those days, restoring, brick by brick, the New York tenements where Cage and Feldman lived, or bringing back their parties, where guests included Robert Rauschenberg and other painters. Yet somehow the freshness of that time came back. In programming the festival, Carnegie’s devoted artistic advisor, Ara Guzelemian, made ideal choices, asking soprano Joan La Barbara to direct the concerts, and Ms. Leng-Tan to join her and the young and fearless Flux Quartet in performing.

All, very simply, were transcendent. Ms. La Barbara, without the slightest fuss, sang and hummed Cage’s vocal music, making me believe I’d always known it. In Feldman’s Structures, Flux — rapt and unerring — hung at the edge of silence. And Ms. Leng-Tan found an extra touch of calm and playfulness, especially in pieces from Cage’s Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano. Here nuts and bolts are stuck between the piano’s strings, to create a gentle, clinking shimmer that seems to come from fairyland, and yet still sounds homemade. Ms. Leng-Tan played with deft, precise delight, as if it all were new to hear, and she could listen with as much joy as all the rest of us.

But then all the music at this little festival seemed new, even after 50 years. So did works of Karlheinz Stockhausen, performed more recently, with composed exhilaration, by Ensemble 21 at Columbia University’s Miller Theater. Thirty years ago, Mr. Stockhausen was a prince among composers, always mentioned side by side with Pierre Boulez. But Mr. Boulez ascended into mainstream fame, while Mr. Stockhausen faded into eccentricity. That made me eager to encounter him again, and in his Klavierstuck IX I entered into something like an altered state. After 144 repetitions of a stubborn chord, two timid little tones emerged, and for a heartbeat, Marilyn Nonken let the music hang suspended, while I wondered if those little notes were some kind of footnote to the opening, or just a momentary pause for breath before the music moved ahead.

Throughout this concert, I found that I had multiple expectations, without ever guessing how they’d be fulfilled. In Tierkreis, a piece about the zodiac, for piano, flute, clarinet and trumpet, nearly everything was high and quiet, but never simple, the instruments combining in a single, four-part line of music, unpredictably embroidered. In Kontakte, for piano, percussion and electronic sounds, a piano chord would catch the taste of an electronic whirr and somehow also match its shape; sounds folded into one another, again creating many-sided, unpredictable events.

These events — Cage-Feldman and Mr. Stockhausen — amazed me. I started making lists of things in them that mainstream composers have yet to really pick up on — silence, or alterations of familiar instruments, or even something boldly simple, like scoring Tierkreis for four musicians, one of whom, the pianist, barely plays.

Which brings me to Great Day in New York, nine celebratory performances jointly sponsored by Merkin Concert Hall and the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center.These succeeded in transcending two familiar problems — the battles that not too long ago were fought among composers who write in difference styles, and the loneliness of new-music evenings, which only hard-core insiders used to go to.Here, like a festival of reconciliation, we had music by 52 composers, all apparently embracing one another, and people really came, even thronging outside Alice Tully Hall, hoping to buy tickets.

I feel, then, like a churl — and as if I’m personally betraying Fred Sherry, the joyful cellist who conceived it all — if now I say that the lack of fighting also meant that nothing very new was going on, that things had reached a comfortable plateau where not much was surprising It’s somehow not a shock that one of the most impressive offerings, a group of songs by Ned Rorem, written in the 1950s, was also the most traditional, since Mr. Rorem did nothing more (but also nothing less) than continue traditions of the even more distant past, with deep feeling and radiant but unpretentious craft.

Besides that, I mostly liked the music that stood apart from the normal concert world, like an excerpt from Peter Shickele’s Piano Quartet No. 2, which brought a friendly, folk-based sound to concert instruments, with enormous verve and wit. David Lang’s Cheating, Lying, Stealing came off as an eruption of exultant, strongly woven noise.

But one work really polarized the audience: David del Tredici’s This Solid Ground, a group of songs-in-progress, which were heart-stoppingly exposed and lush, and sung with an arresting, raw, and nakedly non-classical voice by John Kelly, a performance artist. A critic sitting next to me gasped and refused to applaud. Here was something new and bold, meticulously wrought and quite surprising — qualities that excited me in Cage, Feldman and Mr. Stockhausen, but which Great Day in New York, despite the celebration, mostly didn’t have.

Chris Dohse, Brother’s Blues: Listing Towards The Gist Of Middle Age With John Kelly and David Del Tredici, 2001 Dance Insider, 2001

There isn’t a whole lot of dancing in Brother, the collaborative “kinetic and dramatic song cycle” by composer David Del Tredici and movement artist John Kelly seen Saturday night at P.S. 122. Kelly punctuates his singing with selected gesture — lyrics by himself, Allen Ginsberg, Lewis Carroll and others — while Del Tredici accompanies on piano. Kelly’s taut body imbues his gesture with restrained power and elegance as he sings a hagiography of the urban Queer male experience at the end of the 20th Century. There’s lust in the journey, and loss, and longing; drugs and humor and style and, naturally, a little Joni Mitchell.

The sorrowful highlight of the evening is Paul Monette’s incantatory poem Here. Kelly unrolls a length of astroturf and reclines beside it to croon into the imagined earth of a lover’s grave. A projected image of microscopic t-cells hovers behind him. With simple, theatrical images, Kelly suggests abjection, desecration, and a furious knowledge. He pursues activity with such purpose during the songs’ interstices.

A bird-like sequence of asanas precedes Ginsberg’s poem Personals Ad, a funny, sweet proclamation of being “alone with the Alone” and searching for someone to “lay his head on your heart in peace.” Imagined and remembered and longed for romantic-sexual-spiritual connections unite the songs’ individual vignettes, as Kelly waltzes with the nostalgia and hope of each partner. An homage to Matthew Shepard, although performed with undeniable intensity and a boot scoot to Dolly Parton, veers from the autobiographical tone of the rest of the material and, therefore, seems gratuitous.

In an extemporary monologue, Kelly tells that his first evening -length work, Go West Junger Mann, was done at P.S. 122 in 1984 Several of the art stars of the 1980s East Village have appeared or will be appearing there this Spring, among them Karen Finley and Ann Magnuson. It’s been a privilege to witness their artistic maturity. Brother speaks for a generation of gay men who used to take drugs and who now take medications, or as Kelly puts it at one point, the “gist of this middle age.” A brotherhood of survivors, on a “middle aged adolescent journey.”

Andrew Druckenbrod, David Del Tredici and John Kelly Evoke Gay Life, Love Hardships In Art Songs At Warhol, The Post Gazette, May 14, 2001

Composer David Del Tredici turned the classical music establishment on its head in the ’70s when he turned away from serialism for the lyrical tonality of his “Alice” works.

Virtually all of his output has drawn inspiration from Lewis Carroll’s stories.

Recently, however, he has looked for inspiration not from the literature of the past, but of the living. Saturday night, Del Tredici took to the piano with performance artist, vocalist and poet John Kelly to present a world premiere of sorts: the latest configuration of their collaboration Brother, a theatrical recital.

The evening itself— staged on the second floor of the Andy Warhol Museum as part of its Off the Wall series – actually contained half of a new song cycle similarly called Brother, with lyrics by Kelly.

The remainder consisted of art songs by the composer set to poetry by Carroll, Alien Ginsberg, Jaime Manrique and Paul Monette. Many of the pieces stem from a new release, Secret Music on CRI, showing the new focus of the composer toward an examination of gay life, love and hardships.

Since being included in the CD Gay American Composers in 1996, Del Tredici has embraced gay subject matter more directly.

Indeed, far from the whimsical splendor of the Alice works for orchestra, the song cycle Brother is intimate and immediate.

Kelly’s lyrics snatch content from the annals of real life with emotional directness; its music evokes the trials of the gay man’s modem experience without drowning in sentimentality.

Tonality is not a paint roller applied uniformly, but a collection of brushes depicting inner inspiration.

Take for example the song Brother, which ended the evening.

With rhapsodic figurations recalling Brahms, the piano part creates the expectations of old-fashioned, if pensive lied.

But soon it becomes apparent that tonality, though sincere (not used ironically), doesn’t fetter the singer to convention.

Kelly’s anguished lyrics about a failed long-distance relationship race away from the conservative framework predicted by the opening bars.

Form follows content, and the contour of the music alternates from flowing sequences to blocked chords and empty space, driving to a powerful ending.

With Kelly’s deft use of falsetto and a voice brimming with emotion, Brother capped the concert with commanding artistry and empathy – the final note being the composer counting in Italian to 13, tredici, thus signing his name to it.

Del Tredici’s music and Kelly’s singing could have stood for the standard recital treatment. But Kelly’s histrionics took the concert to a different and effective level.

From singing in only a towel for These Lousy Corridors to collapsing to the ground in Here, Monette’s moving tribute to his partner felled by AIDS, the visuals enhanced the performance.

Only the rendering of Matthew Shepard, in which Kelly re-enacts some of the events of the brutal beating, bordered on trivializing.

There were some problems with the setup on the second floor. The balance was bad, with Kelly’s microphone not turned up enough. Projections on the back of the stage were partially obstructed by the piano, and there were distractions off-stage near the space’s entrance. These, however, didn’t temper the potency of Del Tredici and Kelly’s creation.

David Roman, Comment: Theatre Journals 2000

And when I die And when I’m gone There’ll be one child born And a world to carry on. —”And When I Die,” Laura Nyro

Laura Nyro, the extraordinary singer songwriter, wrote And When I Die in the mid-1960s. At the age of seventeen she sold the song to Peter, Paul, and Mary and thus launched her musical career. Her soulful music helped chronicle the turbulent times of the 1960s, and she was one of the first in a string of successful female singer songwriters to address women’s issues in popular music. You can hear her influence in the music of nearly every woman singer songwriter from Joni Mitchell and Phoebe Snow to Suzanne Vega and Tracy Chapman. Nyro was also one of the first women to have her songs cross over into mainstream radio. Her songs were recorded by Barbra Streisand (Stoney End), The Fifth Dimension (Stoned Soul Picnic and Wedding Bell Blues), Three Dog Night (Eli’s Comin’), and Blood, Sweat, and Tears (And When I Die). Even as these artists scored major hits with her songs, Nyro’s own recordings such as Eli and the Thirteenth Confession, New York Tendaberry, and Christmas and the Beads of Sweat were themselves critically acclaimed. She achieved nearly instantaneous cult status among her thousands of fans.

I listened to Laura Nyro throughout my teenage years. Her music opened me up to a dramatic world that had little to do with the one I was living in South Jersey. At the time, I wasn’t always sure what her songs were about—she sang of sex, drugs, and war; she was a generation older; and she lived in New York City—but they touched a deep chord in me. It seemed the stakes were always very high in her songs, and she sang them with such conviction that they sometimes were almost too painful to hear. Even if I didn’t completely understand the music, its emotional effect on me was palpable. She was a hippie and a feminist, two ways of being in the world that held enormous appeal to me. Apart from Joni Mitchell, there is no other female singer whom I most associate with the formative years of my adolescence. It might sound pat and even drenched in cliche, but I believe listening to the music of Laura Nyro and Joni Mitchell helped me make it through a queer adolescence marked by fear and confusion. Both were a lifeline to something other, something outside the tight constraints of a normal world. Full of mystery and possibility, their music moved me inward so that I could eventually come out.

I stopped listening to Laura Nyro with any regularity shortly after I came out in 1979, when I found a different life soundtrack in disco and club music. She herself seemed to disappear. There wasn’t a high demand for progressive feminist hippie music in the early Reagan years even if there was more the need for it than ever. At nineteen years old, I was beginning to have a life of my own with its own set of dramas. For me, coming out wasn’t simply a sexual awakening; it was also an introduction to an entire set of cultural practices that included, not insignificantly, theatre-going.

The very first play I chose on my own to see—and I went by myself—was Martin Sherman’s Bent on Broadway starring Richard Gere and David Dukes (Fig. 1). It was the January 2,1980 Wednesday matinee performance (Fig. 2). I was on my college winter break from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and I distinctly remember leaving my parents’ house in South Jersey for the three-hour bus ride into New York City. They had no idea where I was going. And I didn’t either, really. I had read about the play, and its story of homosexual oppression during the Nazi era, while in Madison and made the decision right then to get to the New Apollo Theatre once I was back on the East coast. Arthur Bell, one of the most interesting queer journalists of the 1970s, writing in the Village Voice, the week before Bent’s first previews on Broadway/ stated the following:

“it is brilliant theatre, and Bent, without giving away more plot, will be the most controversial and powerful play since Albee stunned us with Virginia Woolf? 17 years ago. Bent is about injustice, courage, and love, as opposed to yet another mundane but well-meaning explanation of what homosexuality is all about. Certainly Gere and Dukes are victims, but ultimately they are proud and victorious.”1

After reading Bell’s column, I knew I needed to be there. I clipped the column and posted it in my room (Fig. 3).

The theatre that afternoon was filled with what was for me an older generation of gay men, all sophisticated and urbane. My previous trips to New York City had been limited to family visits to Colombian relatives in Queens and high school excursions to see Broadway shows such as Jesus Christ Superstar. Bent’s same-sex love story, its emphasis on gay solidarity in the midst of death and oppression, and its insistence on homosexuality as a mark of pride, made an immediate impression on me. Sitting in the theatre with these strangers also made a lasting impression. I had only come out a few months before; I was uncertain and confused but certainly curious about what it meant to be out and gay. In my journal, I wrote that the experience “will forever remain relevant in my life.” Bent and that audience of gay men offered me a means to conceive and imagine a future.

Soon, however, AIDS would change everything. And it did. What else can be said? Now twenty years into the epidemic, and over twenty years since my own coming out, it strikes me that it’s not only my sense of queerness that has been marked by AIDS; my sense of theatre has been inextricably shaped by the AIDS epidemic, too. It’s not just that I was going to lots of performances either about AIDS or about gay life. No, it’s that AIDS informed so much of the theatre that I’ve attended throughout these past twenty years even if the play or performance wasn’t about AIDS. Even the plays that I attended before AIDS I can’t help but recontextualize within its frame. How many of those gay men at the 1980 matinee performance of Bent are still here? I remember once, at the Steppenwolf Theatre Company’s 1988 New York production of Lanford Wilson’s Burn This, sitting next to a gay man whose coughing was so alarming to the audience that he and his partner felt compelled to leave the theatre. Whenever I think of John Malkovich’s blistering performance in Burn This, a performance of tumultuous energy and virtually uncontrollable rage, I also think of the coughing man needing to exercise every possible restraint to keep from interrupting what seemed so uninterruptible at the time. My sense of the performance on stage was eclipsed by this other tragic drama in the aisle.

So many people died in these past twenty years. But to say this is also to recognize the need to say that so many people lived. One of my very favorite performers is John Kelly. His talent is so irrefutable that he defies easy categorization. This year Kelly was awarded the prestigious Cat Arts/Alpert Award for dance and choreography, but he could have easily won in nearly any of the other categories. I’ve been attending his performances since the late 1980s. I’ve seen him perform his various drag impresarios, including Dagmar Onassis, in queer clubs and bars in New York and Provincetown. But I’ve also seen him perform his work at more established alternative venues in New York such as La Mama, Danspace at St. Mark’s at the Bowery, and the Ohio Theatre and also at Seattle’s On The Boards. You might have seen him on Broadway during the 1999-2000 season as Bartell D’Arcy, the opera singer, in James Joyce’s ‘The Dead’ or in the touring company that played in DC or LA, where I caught it. When he sang the Italian aria to the dying Aunt Julia, he virtually stole the show. Or you might know him from his signature performance as Joni Mitchell in Paved Paradise, a performance so exquisite that Mitchell herself was moved to tears. His artistic versatility is legendary in the downtown arts scene, and deservedly so. It’s hard to think of another performer who has so successfully maneuvered through so many different artistic disciplines. He is, for me, among the most interesting artists alive.

John Kelly has been HIV-positive since 1989, but like many artists of his generation, he has refused to allow his HIV-status serve as the primary means to understand his art. In 1998, he told Poz, a magazine on HIV/AIDS issues/Tm not an ‘AIDS artist,’ I’m an artist coexisting with HIV. It’s a part of my life, but I’ve never felt I’d succumb for one minute.”2 Later, however, in the same feature, Kelly would explain, “AIDS informs everything I do.” He has created at least five full-evening interdisciplinary AIDS pieces, works that combine song, movement, image, and text. “I didn’t feel my place was in the streets protesting,” he offered as an explanation of his work, “but onstage, making pieces about AIDS, dignifying drag, singing in a high voice. It’s a kind of activism, on my own terms.”

Recently I flew out to New York from Los Angeles for a theatre weekend and to see two performances in particular. Theatre-going remains for me among the most intense and worthwhile practices of my life. There is great theatre in Los Angeles, the city where I live, as Meiling Cheng’s essay on Highways Performance Space in this issue attests. But certain events, as we are all well aware, play only in New York. The two productions I wanted to see were running there for limited engagements. Beyond that, as if it needs any excuse, flying across the country for a theatre weekend is about as thrilling as anything I’ve ever done. Admittedly, it’s also quite extravagant. But we all have our priorities and live accordingly. This is one of mine. I got my cheap United Airlines tickets on-line that week at half the price and set off for New York City.

I traveled across the country to see a performance that was, in fact, already sold-out for the weekend. Unwise, to be sure. No, I wasn’t trying to secure tickets for The Producers; what I was hoping to see was a new musical theatre piece based on the songs of Laura Nyro (Fig. 4). Eli’s Comin’ was having its world premiere at the Vineyard Theatre in a production directed by Diane Faults and with vocal and orchestral arrangements by Diedre Murray.3 Laura Nyro died of ovarian cancer in 1997. She was 49 years old. Since then various artists have tried to keep Laura Nyro’s legacy, which is to say her songbook, alive.4 Eli’s Comin’ comes out of this context. I wanted to support and witness this project, and I knew I’d enjoy the performance. So I arrived ticketless at the theatre. I got there early to wait in line for cancellations. Other than the Vineyard theatre staff setting up for the evening, it was just me and an older man waiting around in the lobby. Eventually he and I got to talking, the staff alerting him that I was in from Los Angeles to see the show. It turned out that he not only had an extra ticket; he was, in fact/ Laura Nyro’s father. For the next thirty minutes we spoke of Laura’s music/ the untimeliness of her death/ and the terrible irony of her mother’s death also of ovarian cancer and also at the same young age. Lou Nigro/ Laura’s father/ wanted to hear what his daughter’s music meant to me and why I would travel from Los Angeles to see this performance.

AIDS has taught me—or would it have come to me in time regardless?—to be present for the moments in my life that matter most; to recognize and value them as they occur; to pay attention to these surprising moments of heightened emotion/ moments of shared human intimacy and profound connection, however temporary. I loved Eli’s Comin’ for many reasons: the talented young cast members were phenomenal, the musical arrangements were lovely and heartfelt, and the songs were as masterly and enigmatic as I experienced them many years ago. It was also enormously poignant to see a new generation of women singing these songs to sold-out intergenerational audiences (Fig. 5). But it was seeing the show with Laura Nyro’s father that made the event especially memorable for me.

Lou Nyro, who lives in New York City, attends every Saturday evening performance. His daughter’s spirit lives on in her music and in these performances of Eli’s Comin’. His theatre-going is a way to honor his daughter and be in the company of others who also share that need. He explained to me that it was very important for him to be there for his daughter, for the cast, and for him, too. For me, Eli’s Comin’ returned me to an emotional landscape unfiltered by AIDS, it brought me back to a time in my late teenage years when my own sense of alterity was being shaped by forces seemingly outside of my control. I don’t always want to revisit that period of my life. It was a difficult period that estranged me from my family and threw into crisis my sense of home. Tellingly, the only journal I still write is my theatre journal, where I record all that I’ve seen. These theatre journals provide the time-frame for my life; they help organize my life experiences in a chronological system that begins for me pretty much with Bent.

Eli’s Cumin’ helped me realize that something else was also at issue for me these past twenty years. I haven’t allowed myself to revisit this earlier time not because my life was so terribly fraught then, but because during that short period between coming out and the arrival of AIDS/1 was able to be live as a gay man in an AIDS-free world. Rather than revel in that past, I have repressed it in order to focus on dealing with AIDS. So much of my energy these past twenty years have been directed toward that reality.

I never saw Laura Nyro perform her own music. My experience of her was always in the isolation of a closet that others called adolescence. But it was also a music that made me tremendously happy, a music I would sing and dance to alone in my room. Here now, in New York, with her father by my side, and with so much time and death laid out before us, I was hearing her songs anew and revisiting an earlier version of myself that was, perhaps, too distant to recognize up until that point. I can’t begin to imagine what was going through Mr. Nigro’s mind during the performance, and it seems equally unlikely that he had any idea what was going through mine at the time. But each of us knew that we had heightened the experience for the other. We told each other as much before parting our separate ways and pouring back out into the city. Theatre-going produces unpredictable effects, subjective associations, and fleeting exchanges that are not based solely on the content of the production. These oblique and unforeseen connections underline the way our personal histories surface and sometimes intersect within the space of performance.

The other performance I flew out to see was Brother, John Kelly’s latest production, a collaboration with the composer David Del Tredici, at PS 122 (Fig. 6). Brother, a song cycle for countertenor and piano, sets to music the poems of Alien Ginsberg, Jaime Manrique, Paul Monette, Lewis Carroll, and John Kelly. Del Tredici and Kelly share the stage, with a piano at stage left and a writing table at stage right. Each song, while staged differently, builds on the association of the others. Subtitled Songs Your Mother Never Taught You, Kelly and Del Tredici focus on gay male subjectivity, especially on feelings of love. It’s a fascinating and seemingly unlikely collaboration that brings together two artists at the height of their careers, one a Pulitzer-Prize winning classical composer and the other a double-Obie winning performance artist. Kelly theatricalizes and all but reinvents the traditional form of the musical recital. He sings, dances, plays guitar, changes costume, shows his original artistic videos as well as archival footage of previous performances, and even choreographs for himself a Western line dance.

Midway through the performance, Kelly sings Paul Monette’s poem, Here, the inaugural poem of Monette’s heart-wrenching 1988 collection of poems. Love Alone: 18 Elegies For Rog, written shortly after the death of his lover/ Roger Horwitz, in 1986. Here is about loss and survival. Paul begins the mourning process even before Rog dies. Midway through the poem, Monette writes the following:

Oh sweetie will you please forgive me this that every time I opened a box of anything Glad Bags One-A-Days KINGSIZE was the worst I’d think will you still be here when the box is empty Rog Rog who will play boy with me now that I bucket with tears through it all when I’d cling beside you sobbing you’d shrug it off with the quietest I’m still here5

The poem, which continues for another ten lines, is like all others in the collection, unpunctuated. Monette wanted to capture the rawness and incomprehensibility of his emotions during Roger’s illness. Monette leaves a record of Roger’s voice in the poem, which becomes, after Monette’s own death in 1995, the poet’s own. They are both still here in the poem itself. Kelly very effectively brings voice to both these men in his beautiful rendition of Here, a moving act of testimony to all those lost to AIDS and an acknowledgement of those left behind. Someone, the poem suggests, is always still here. Someone moves forward and bears witness to the lives lost. The poem—like the song in Kelly’s performance—showcases the role of the arts in response to AIDS and foregounds this role as an ongoing necessity that continues twenty years into the epidemic. In the preface to the collection, Monette insists that he “would rather have this volume filed under AIDS than under Poetry, because if these words speak to anyone they are for those who are mad with loss, to let them know they are not alone. Kelly and Del Tredici honor this sentiment and recirculate it for our time.

Close to the end of evening, Kelly tells his audience that this is his first return to PS 122 since the mid-1980s. For him it was a kind of homecoming since PS was one of the first venues to support him as an artist. He seemed genuinely happy to return to the space for it provided him the opportunity to consider his own artistic and personal journey during the past two decades. As someone who sits in Kelly’s audience often, I was enormously pleased to bear witness to Kelly’s survival. I wasn’t always confident that either one of us would still be here so many years and performances later. Theatre-going might evoke, as Herbert Blau argued close to twenty years ago, a sense of mortality, insofar as we are, in his view, watching the performer dying onstage. But, as Jill Dolan points out in her essay on theatre and utopia in this issue, this insight can motivate audiences to consider their mortality on different terms than those Blau imagines.7

Catching Eli’s Comin at the Vineyard Theatre and watching John Kelly perform at PS 122 underscored the reasons why I love going to live performance. There’s always someone else there on the stage and in the room with me. Seeing live theatre requires live bodies on the stage and in the audience. Yes, we might be dying in front of each other, but we are also alive together too. In the case of these performances, the living gather to honor those recently gone and share with each other their lives for that moment in time. As Laura Nyro sings, “there’s a world to carry on.”

3 Eli’s Comin’ was created by Bruce Buschel and Diane Paulis and opened at the Vineyard Theatre on May 7, 2001. The Vineyard Theatre is among New York City’s most important Off-Broadway venues. In the past they have premiered new work by our most accomplished playwrights including Paula Vogel, Craig Lucas, and Edward Albee. In 1998, The Vineyard received a special Drama Desk Award for sustained excellence and a special Obie award for sustained excellence.

4 There’s a terrific tribute compact disk. Time and Love: The Music of Laura Nyro (1997 Astor Place Recordings, TCD 4007), that came out shortly after Nyro’s death with cover versions of her songs by Sweet Honey in the Rock, Roseanne Cash, The Roches, Jane Siberry, well over a dozen women artists giving her props by singing her music. Peter Gallway, the project’s producer wrote the introduction to the recording which calls attention to her place in musical history: “Laura changed the face of popular music. What Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and Joni Mitchell did to kick open the doors of personal truth, Laura magnified a thousand-fold for a pop, street corner sensibility of feminine vulnerability, power and passion. That torch has been carried by the women in this collection—through their courage, their interpretation, their freshness, their singular passion.” Roseanne Cash makes the point of Nyro’s influence more explicit and personal when she writes in her tribute published in the liner notes: “Laura Nyro is a part of the template from which my own musical and Feminine consciousness was printed. In the back of my mind, I knew Laura had done it, even before I was sure what “it” was. It turns out that “it” meant making no apologies, not being a victim, celebrating the voice and exploring how the voice connected to being a woman in the real world.”

”Paul Monette, “Here,” Love Alone: 18 Elegies/or Rog (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988), 3.

6 Monette, “Preface,” Love Alone: 18 Elegies for Rog, xii.

7 Herbert Blau, Take Up the Bodies: Theater at the Vanishing Point (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1982). See also Jill Dolan’s “Performance, Utopia, and the ‘Utopian Performative'” in this issue. ,Clifford Chase, “Just His Imagination,” POZ, May 1998, 54-55.

Arthur Bell, “Bell Tells,” The Village Voice, 14 November 1979, 25.